Through my career in software, I've come across a broad range of attitudes and opinions towards testing code. The two extremes being that 'tests aren't worth writing because something is too complicated', or that 'every single piece of code being checked in should be accompanied by tests'. Of these two contrasting opinions the latter, although not always in such an extreme form, is much more prevalent. Here, I will argue three cases why we don't always need to test code: the obvious correctness isolated pieces of code can have; the redundancy badly coupled tests can experience when refactoring; and the often immutability of business-critical code. Instead, I believe that we should be carefully considering where tests truly are required before implementing any.

The Obvious

If you have ever taken a tutorial, watched a course, or read a book on unit testing, you have probably seen an example that tests a piece of code along the lines of the following:

func Sum(x int, y int) int {

return x + y;

}

No doubt you'll then go on to be shown exactly how you'd write a test that checks a variety of inputs to make sure the

Sum function produces the right results for every possible case you can think of.

What these tutorials all fail to consider though, is whether the function requires a test in the first place. Having a look at the above example, do you think there's any possibility it's not doing what it claims to be? Could it be expressed in a simpler way? Is it hard to wrap your head around? The answer to all three of these questions is (hopefully) no. This illustrates how code can be intuitively correct at a glance, without the need for extensive proof or testing. Sir Tony Hoare, a hugely influential computer scientist, infamously said the following:

“There are two ways of constructing a piece of software: One is to make it so simple that there are obviously no errors, and the other is to make it so complicated that there are no obvious errors.”

This piece of rhetoric fits in perfectly with the questions we asked of the Sum example. In practice, we can see that

tests are only really needed when something is 'so complicated that there are no obvious errors'. These tests would then

prove value by showing that these non-obvious errors don't exist. So for simple, 'obviously' correct code, is there any

need to add tests? Instead, before adding tests, you should ask the question: 'Is this code obviously correct, or can I change

it make it obviously correct?'. If the answer to this question is yes, then there is no need to test what is obvious.

The Coupled

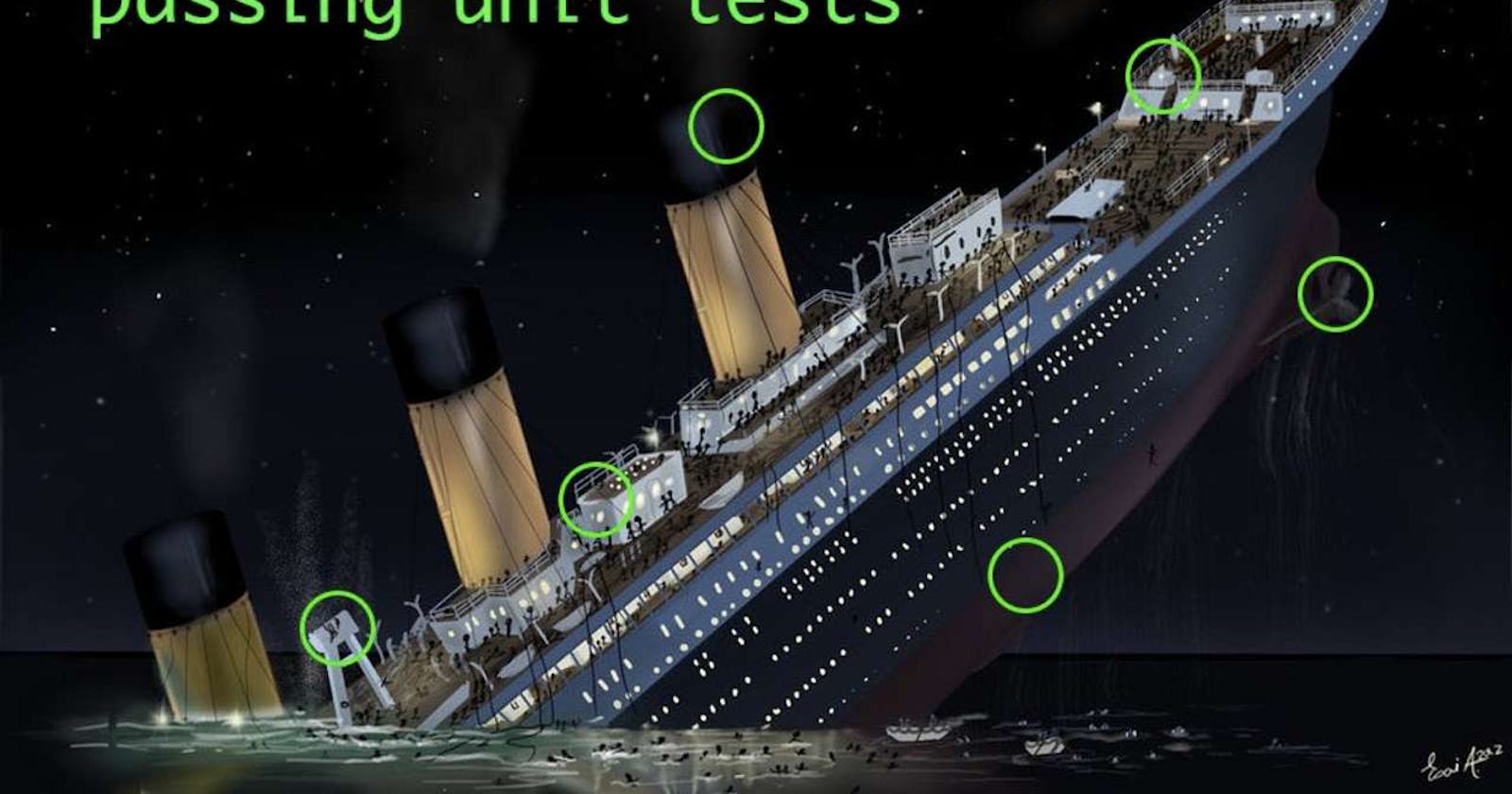

When deciding on what level of tests to write for a system (unit / service / ui / integration / end-to-end, or various other names), the 'Testing Pyramid' immediately springs to mind. If you haven't seen the idea before, it suggests that we do the majority of our testing at the individual 'unit' level, This unit-level results in tests are fast to run and can quickly, cheaply and efficiently provide a high level of code coverage. We should then provide higher-level tests in a much sparser manner, relying on these to effectively prove that everything is wired up and communicating properly, rather than for checking individual branches in logic.

This system is straightforward and initially makes complete sense. It is also the commonly accepted practice. However, it fails to acknowledge that the disposability of code, or the ability to refactor can be a major consideration in what tests to write and how to write them. Any system undergoing continual work will see units, or isolated pieces of code appear, disappear, and take completely different forms over time. This is the natural progress and evolution of working, living software. To emphasise this point, I ask 'have you ever refactored a section of a codebase, to find that existing unit tests are made completely irrelevant or redundant?'. If so, this shows that the initial tests were overly coupled to the layout and structure of the code. Remember that tests are simply more code that agrees with the initial code you just wrote (or if performing TDD, they are simply more code that agrees with the code you are about to write).

In areas of code that are rapidly and constantly changing in structure, higher-level tests provide a greater level of maintainability and stability, as the higher-level workings of a system are typically more stable. These tests are significantly less likely to be made completely redundant.

This, however, poses an interesting conundrum: how do we know when code is likely to change in structure or approach in the future? If we could identify these areas ahead of time, then our newfound prescience could simply mean we write them in a better form the first time around. Sadly, however, we are left fumbling in the dark: attempts at organising code are a 'best efforts' approach given a current state of knowledge.

We do, however, get an increased understanding of a system the longer it exists, or the longer we work on it. This allows informed decisions about what testing is fully appropriate. Young systems or systems with a high degree of uncertainty benefit the most from high-level 'black-box' style testing, as these are the most likely to undergo structural change over time. These tests are much less likely to risk redundancy. Contrastingly older, more stable, or better-understood systems benefit more from the flexibility and efficient coverage that unit testing can provide.

Overall, the age, stability and uncertainty of a system need to underpin what tests we write: the testing pyramid provides an oversimplified view of the world, but a useful tool to consider. However, we need to supplement this with our understanding of code and its evolution over time, asking 'how long will these tests be relevant for?' or 'are these likely to be irrelevant in X months/years time?'.

The Immobile

On many of the large scale software projects I have worked on, a rather interesting irony has been present: the most important, business-critical pieces of code are often the most insufficiently tested. Their outputs lack clear definition and seemingly any small change could spell disaster. Yet however, they remain this way.

Several years ago I worked on an NHS project. This was, to massively oversimplify, an incredibly complicated and fundamental system responsible for associating prices with hospital treatments and generating reports based on these prices. The reporting system was well tested, with thousands of tests meticulously checking every single possible output for a massive variety of inputs. Despite all this, the core of the project, the pricing system, was almost entirely lacking in tests. It was only truly tested as a side-effect in testing the reports. The code was incredibly hard to work with and was not amenable to testing, and so it never was. At the time I didn't understand how it could be left that way when it was such a fundamental part of the system.

I've later realised the rationale is incredibly simple. The original code was written as a proof of concept. It worked, and as a result, became the production code. Nobody wanted to make any changes for fear of causing an unknown regression that could be incredibly difficult and costly to track down and fix. Similarly, the process for assigning a price was a fixed piece of logic: it didn't change over time, no new requirements changed how it worked, and nobody really needed to know how it worked internally - just that it did. The cost of not having any tests, even for such an important piece of code, was massively outweighed by the risk in changing the code to make it testable and the effort in testing it.

Am I advocating not testing crucial business systems here? No - not at all! However, it's important to recognise that we don't live in a perfect world. Systems missing tests for crucial parts exist everywhere and are far more prevalent than I'd like to admit. However, this isn't the catastrophe younger me thought it was. If a piece of code is complicated, but it works and never changes, then does it matter if it is poorly tested? Adding tests when making changes, however, would still be prudent - but we can still ask the question: 'does the benefit of testing this piece of code outweigh the difficulty of adding tests?'. It's a dangerous question to ask, and the answer is almost exclusively 'yes - add the tests'. But just maybe, sometimes, it's a worthy thing to consider.

To Conclude

The approach to creating well-designed test suites that provide continual value throughout the lifecycle of a project is a difficult task. Advocates of a 'testing pyramid' approach oversimplify the matter. While the intention is good, it fails to root itself in the practicality of the ever-changing world of software development: the evolution of code over time can easily render tests redundant or unnecessary, and at times those tests can even be a barrier to refactoring. The 'obvious' nature clean code can possess also reduces the need for tests as a proof of correct behaviour. Similarly, a simple cost-benefit analysis should be considered when regarding existing code that is known to be correct and is unchanging, or changing very infrequently. Not all tests are worth writing. Not everything has to be tested, and that is fine.